The D&L Blog

Another Historic Transportation Route

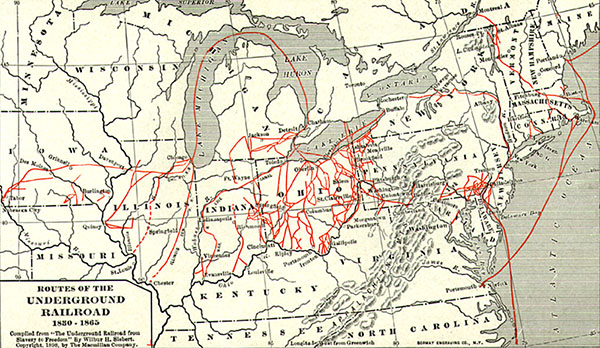

While the exact dates remain unknown, the general belief is that “Underground Railroads” began popping up in the late 18th century1, and continued functioning until the end of the American Civil War. However, for the years before, enslaved individuals had few better options than to travel complex routes that followed hidden roads and rivers; few better options than moving discretely between churches, privately-owned homes, and institutions friendly to the abolition movement in the cover of the night2.

Along the Underground Railroad, those that guided the way were called “conductors” with the various stops called “stations,” “safe houses,” and/or “depots.” The people operating these locations were called “stationmasters.”

Due to its strategic location as the first “free” state north of the Mason-Dixon Line and the fact that it had a large Quaker population, the first organized white European group to actively assist enslaved individuals1, Pennsylvania was instrumental for many journeys north, with key conductors like Harriett Tubman and Robert Purvis utilizing its various stations throughout their trips.

While Philadelphia is one of the older and more famous stations, with Quaker abolitionist Isaac T. Hopper setting up a network in the early 1800s, the road was long and traveled throughout the majority of Bucks County as well.1 If you would like to travel to any of the locations mentioned, or learn about other stations and stationmasters, you can find driving instructions and more information at the end of this blog.

Bristol

Outside of Philadelphia, Historic Bristol Borough was just one of many stops along the Underground Railroad as formerly enslaved individuals began making their way north towards freedom.

Within the borough of Bristol, there are a variety of historical sites and museums to visit, with one of the most famous being The Harriet Tubman Memorial Statue in Basin Park. The statue points north in the direction of Polaris, the star that often guided her on her journeys.3 It is a monument to her bravery and courage, remaining one of the most famous art installations dedicated to the Underground Railroad in Bucks County.

A lesser-known story, but one just as important is that of Dick Shad. Formerly known as Richard Russell, Dick was enslaved by Colonel Richard Russell on a plantation in Virginia during the late 1700s. After learning English fluently and biding his time, he managed to escape from Virginia, finding refuge with a Quaker farmer in Langhorne (another significant stop along the railroad).4

Over the next decade, Dick would drop the last name Russell and became known as Dick “Shad,” for the fish he sold during the winters. He saved his money and built a family before finally settling in Bristol where he constructed a home and established a hack-line — “a horse-drawn carriage to ferry people around for a fee.”5 Unfortunately, it was during one of his rides that a man from the south would recognize him and quickly go on to inform Col. Russell.

What followed was a legal battle for freedom that, thankfully, Dick won.

After much negotiation and public debate, Dick Shad was allowed to remain free after Col. Russel received the pocket watch that Dick had grabbed as he escaped, and $350 that had been collected in a community-wide effort (approximately $10,350 in 2022 currency6).

Bensalem

Heading slightly northwest, you’ll enter the township of Bensalem where you can find the Little Jerusalem African American Episcopal Church7 , also known as the Bensalem AME Church. Nearing 200 years old, the AME Church is the oldest African American church in Bensalem and is one of many AME churches that served as stations for those travelling the Underground Railroad.

The Bensalem AME Church and its associated farm often served as a key stopping point for Robert Purvis, an integral figure to the abolitionist movement and a founder of the American Anti-Slavery Society. It is estimated that he assisted approximately 9,000 individuals in their escape to freedom, making him one of, if not the most important conductor in Bucks County History.

The Bensalem Church still holds services and has a Facebook that can be found here: @BensalemAME

Yardley

Travelling back east and farther north, you reach Yardley.

One of the first things you’ll learn about the Underground Railroad is that it is not, in fact, a railroad that was built underground. The usage of the word “underground” references the necessity for secrecy, rather than its physical location. However, when you pass through Yardley on this journey, you’ll find an establishment that actually does delve beneath the surface – The Continental Tavern.

Previously known as the Continental Hotel in the 1800s, this inn is one of several establishments in Yardley that was connected by a secret system of underground tunnels. These passageways were all built with the purpose of helping former slaves escape in the most discrete way possible.

While many knew that the hotel served as a way station for the Underground Railroad8, it wasn’t until 2007 that new owners and renovation plans uncovered a secret chamber leading to a “5-foot diameter cylindrical stone tunnel which went deep into the ground.” (Interesting Note: the chamber was also used to store liquor during prohibition in the 1920s).

It would later be discovered that this tunnel connected to the establishments that are now known as the Yardley Grist Mill and the Lakeside Home.

New Hope

Continuing north is New Hope, one of the final stops along the Underground Railroad within Bucks County. There are two stations to pass before ending this particular journey through history.

Mount Gilead Church is, like Little Jerusalem, one of several churches that joined together to create the first and oldest all-black congregation, the AME, under Bishop Richard Allen from Philadelphia. This church would become an integral station along the Underground Railroad with refugees flocking from Maryland, Delaware, and the Carolinas. Most famously, Benjamin “Big Ben” Jones, a former enslaved person who was sold-out by a white resident and recaptured for a period before ultimately being “repurchased” by the community that had come to love him, regaining him his freedom.10

1870 Wedgwood Inn of New Hope is one of the northernmost points of the Underground Railroad within Bucks County and Pennsylvania. The Victorian style house was originally used as a storehouse during the revolution, with weapons stored in the cellar. This made it an excellent location for a stay station. The Wedgewood Inn is actually another location that connects to a system of underground tunnels. This system would ultimately allow passage to the Delaware Canal (an area still accessible along the D&L Trail) where individuals would travel seven miles north to Lumberville.11

Reaching the End or Continuing On

At this point, individuals would either find refuge in more welcoming communities within the state, or cross the Delaware River into New Jersey and continue the journey towards Canada.

Traveling further north and on to Canada was generally the end goal. Across the border, formerly enslaved individuals were no longer at the mercy of the fugitive slave laws that were so rampant throughout the states.12 Because unfortunately, escaping from the south didn’t always mean freedom.

The slave catching business was lucrative and merciless. There are several instances in which free men were captured “by mistake,” and others where formerly enslaved individuals were mortally wounded during or after they were brought back. Fugitive slave laws also made it that assisting “fugitives” was a severe crime. Stationmasters that were caught could end up in jail, or fined $20,000 (approximately $591,818 in 2022 currency).

But for those that believed in the abolition movement, it was worth it.

At the end of the day, stationmasters, conductors, abolitionists- they all knew they were fighting for what was right, and their bravery remains evident in the buildings, the tunnels, and the communities that stand to this day.

**For more information check out Visit Bucks County. To travel the stops located in Upper and Central Bucks County, follow these driving directions. Take the tour in Lower Bucks County with these driving directions. **

Sources

- https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/underground-railroad

- https://www.visitpa.com/article/destination-freedom-traveling-pas-underground-railroad#:~:text=Not%20an%20actual%20railroad%20at,many%20entry%20points%20to%20freedom

- https://www.ydr.com/in-depth/news/2019/10/29/harriett-tubman-underground-railroad-path-slavery-escape-pa/3863408002/

- https://www.thereporteronline.com/2008/01/30/our-link-to-the-underground-railroad/

- https://www.buckscountycouriertimes.com/story/opinion/columns/2015/02/02/lavo-slave-trial-that-rocked/18090043007/

- https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1828?amount=0.44

- https://gis.penndot.gov/CRGISAttachments/SiteResource/H001688_01H.pdf

- https://contav.com/about/

- https://contav.com/about/history/

- https://soleburyhistory.org/on-line-exhibits/interactive-maps/underground-railroad-stops/mount-gilead-church/

- https://www.wedgwoodinn.com/inn-renovations.html

- https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/fugitive-slave-acts

- https://www.visitbuckscounty.com/things-to-do/planning-ideas/underground-railroad/

**Brought to you by a project made possible in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities. The views, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this post do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.**